Hippodrome Cinema Coordinator Discloses Former Israel Residence Following “Israelism” Screening

On March 26, Gainesville Jewish Voices for Peace (JVP) hosted a screening of the film “Israelism” at the Hippodrome Theatre.

The film follows If Not Now founder Simone Zimmerman and a former Israeli soldier only identified as “Eitan,” telling how they turned away from supporting Israel due to human rights violations against Palestinians.

Hippodrome Cinema Coordinator Adam Azoulay chose to show the film with approval from his supervisors.

Following the screening, Azoulay and a JVP leader led a discussion with other Jewish film-watchers about how the movie related to their lives.

During the discussion, Azoulay stated, “This is like watching my life story. I’m a millennial, I went to a Jewish school, and I was indoctrinated in these ways. It wasn’t until I lived in Israel for two years, and it wasn't until 2015 that I became de-radicalized. I feel like I don’t have a lot of power to make geopolitical change, but I run a movie theater, so one thing I can do is show these important movies.”

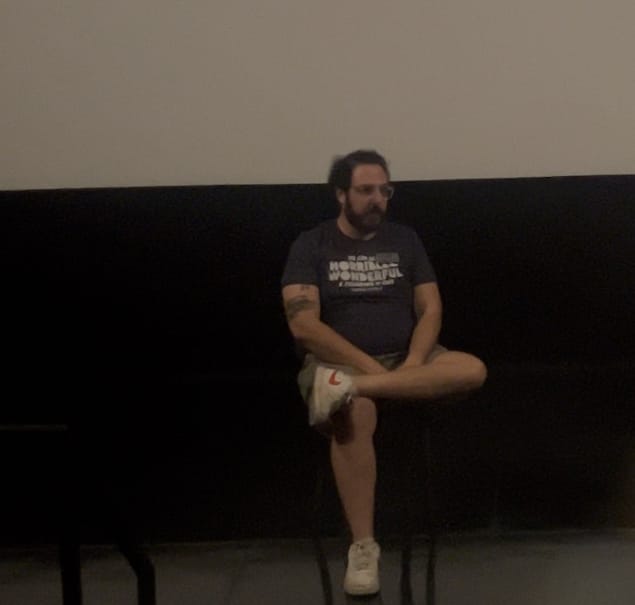

Adam Azoulay talking about how the film “Israelism” is similar to his own life (GnvInfo)

Azoulay said that he lived in Israel from 2010 to 2011.

Azoulay went on to say, “For me, living there was really strange because, as this movie shows, the indoctrination you go through and how it builds it as this utopia, a Jewish utopia. Then when you get there, the reality is—that was the first time I saw Jews being racist against other Jews…. Not even to say what they do to the Arab population there. That was definitely eye-opening living there.”

Adam Azoulay talking about his thoughts after living in Israel (GnvInfo)

The day after the screening, GnvInfo conducted the following interview with Azoulay.

Q: How did you get hired as the film coordinator for the Hippodrome?

Azoulay: I worked here as a house manager. I did that for about six months, I think. That job was really easy. I worked from home, so I was looking for something where I could come back out into the community because I was just at home all day. I was like, ‘Well, they’re always hiring at the Hippodrome,’ for this entry-level job, which was House Manager, where you are responsible for opening up the building. After doing that for a while, I was like, ‘Oh, I noticed your cinema was closed. Is there any particular reason?’ They said to me, ‘No,’ there just wasn’t anyone to run it…. They asked if I wanted to run it, and I said, ‘Sure.’ That’s kind of how I got that job.

Q: What are the main responsibilities of being the film director?

Azoulay: My main responsibilities are choosing the films, deciding on the program, and then managing certain staff, who are my projectionists. They're the ones who actually run the whole booth. I guess the broader, you know, job is just to make sure that people in the community are enjoying the theater and are engaged with the cinema.

Q: Do you have to get any, like, final approval from any other staff members before a film is shown?

Azoulay: Yeah. I have supervisors, and so about every month, I send out the program that I'm gonna do, and then everybody gets to look at it and give me feedback on it. Then after that, if I don't hear anything, I go ahead with the program.

Q: Do you know what kind of influence the Hippodrome donors have on what films are shown?

Azoulay: So right now, none, I hope. You know, even the donors that complained about films, you know, they've gotten to me and said, you know, ‘We don't wanna necessarily change what you're doing, but we will still, you know, condemn whatever we disagree with.’ It's been kind of a clusterfuck dealing with a lot of the stuff around programming recently.

Q: Are you able to tell me anything more about that cluster?

Azoulay: Straight up, like, you know, if I get fired from here or don't work here anymore, then I'm happy to spill all the tea. But right now, yeah, I can't really talk that much about it.

Q: Are you still doing work in law while working here too?

Azoulay: Yeah. This is a part-time job, so I still have my day job.

Q: Where did you grow up?

Azoulay: I’m from Miami.

Q: Since we were watching the film “Israelism” yesterday, you were talking a little bit about your background. What did your family teach you about Israel growing up?

Azoulay: It's a bit of, you know, both sides. My dad was always an anti-Zionist. My mom kind of bought in a little more to the propaganda. I grew up really confused about it generally. Yeah, that's kind of where my family background is.

Q: How old were you when you moved to Israel?

Azoulay: This would have been 2011. I'm trying to think. I went for a study abroad. I did a study abroad program there for, I wanna say, two semesters. I think I was 25 [years old].

Q: Did you stay there after, and also, what program was that?

Azoulay: I went to film school for my undergrad. I worked in the film industry in Florida for a long time. I was deciding between going back to get a degree in cinematography or going to law school. They offered, they have, you know, because of the way Israel is trying to recruit Americans, essentially, they offer a lot of free school options. There was this free photography program that I could take advantage of to study abroad. After it was over, I didn’t stay because I became really disenchanted with the whole country there.

Q: How do you feel looking back, taking on that program? Palestinians don’t have that opportunity, and you were able to take that opportunity.

Azoulay: Absolutely, yeah, it's awful. All of this stuff, especially the movie yesterday, I think “Israelism” shows you the ways the American Jewish population is used to further the Zionist agenda. You do feel used, and you do feel like, yeah, once you know what's going on, you start to realize the lack of equity, the lack of equality, and also the lack of human rights for Palestinians. Not only are they not given those opportunities, they're not given food and water and the ability to live their lives. They essentially live in one half of the country, an apartheid state, and then the other half, an open-air concentration camp.

Q: Yesterday I thought you said you were there for two years?

Azoulay: It was between those two years, so I think it was a total of six months, but it was like 2010-2011.

Q: Did you go back and forth?

Azoulay: No, once I was there, I was pretty much just there.

Q: After the program, did you leave?

Azoulay: Yeah, I went back to the states and went to law school.

Q: Where were you?

Azoulay: The school is in Tel Aviv, which, like they said in the movie, is right next to the Palestinian city Jaffa…. The people that are living there are living as, like, second-class citizens; it's really troubling. I mean, nothing will make you an anti-Zionist faster than spending time in Israel.

Q: Did you ever participate in—you know how we saw those Israeli war games yesterday in the movie? Did you ever?

Azoulay: I never went to summer camp, so I never really did anything like that. As far as my upbringing, I never did any military. In general, I'm not really supportive of the military. That movie had a lot of Americans who are used to coming over there and being a mercenary army where they brutalize Palestinian people. I, fortunately, I guess, I don't know, never had wanted to ever do that or never got exposed to that side of it.

Q: I was looking a little into the Breaking the Silence organization [as they were featured in the film]. They don't explicitly oppose military refusal. They say something along the lines of “everyone opposes the occupation in their own way.” What is your stance on military refusal?

Azoulay: Like with Israelis refusing to join the army? I mean, again, I don't know. I think the IDF is like— I mean, we see proof every day, but the IDF is, as far as I'm concerned, terrorizing these people. Anyone who refuses to join is probably on the right side. Whatever their politics are about occupation is, I don't know, a different question. But, yeah—you know, I think that the fewer people the IDF can use to brutalize, the better.

Q: What examples of apartheid did you witness when you were there?

Azoulay: When I was there, I was not in any of the West Bank territory, so I didn't see firsthand this one right for certain people and then another set of rights for other people. But I will say, just in general, in Israel, the atmosphere is that anyone of Arab descent is a second-class citizen. You know, you can just see the people in Jerusalem or people in Jaffa, Acre…. The Palestinian populations are still in those cities, but they’re not treated with the dignity that they deserve.

Q: Do you remember how they were treated? Like, any examples of the way Israeli soldiers or settlers would treat them?

Azoulay: I think the movie does a good job of showing it to you, but it's that idea that the military is everywhere. It's a Big Brother-watching kind of thing. The fact that they're everywhere makes you paranoid. That’s their goal, to make you scared all the time, and putting Palestinian people in that level of stress is unconscionable.

Q: Did you have any personal interactions with the Israeli military when you were there?

Azoulay: Not me particularly, but it's hard to say. They’re everywhere. When you’re riding the bus, there are soldiers with AK-47s. Anywhere you go, they’re everywhere. I think that one of the things that's really complicated is that there's mandatory conscription there. A lot of times when you're talking about Israelis and you're talking about the levels of complicity, you have to remember that it is a fascist country. Like, the military's conscription is mandatory. Whatever is in the hearts of these people, eventually they’re going to brutalize Palestinians. It's the entire country; everyone goes through military service.

Q: Did you believe at the time that you had a divine right?

Azoulay: I've never believed that. Absolutely not. I'm not that religious, so I don't believe in God. Since I don't believe in God, I definitely don't believe in any divine rights.

Q: You work with your mother in your law firm. I saw on the website that she lived in Israel for seven years. Does that coincide with when you lived there?

Azoulay: No, that was her youth. That's why I've always had, like I said, this two-pronged thing because she lived there for a time and kind of bought into the utopia aspects until she left. I think it's like a lot of people—the propaganda that you get from Israel paints a super rosy picture. Then when you go there, it's like an unmasking. You see that the picture is not at all like they claim it is.

Q: You said you didn’t fully turn away from Zionism until 2015, right? That’s a little after—a few years after you left?

Azoulay: I was never like a Zionist. I would say I didn’t become an anti-Zionist and support Palestinian people directly until I saw that Trump was gonna get elected, and he was gonna give the Israeli government carte blanche to just go in and massacre everybody. It was at that point that I was like, ‘I can't be silent anymore. I have to get involved in activism.’

Q: How do you feel like you weren’t a Zionist when you were taking advantage of the Zionist system? When you took advantage of their programs?

Azoulay: It's not something I’m proud of. It’s not something I’m happy about, but at the time—you know—we’re all struggling with student debt and trying to get our education. At the time someone was offering me free education, and I didn’t know much about the Palestinian struggle at that point. But living there opened my eyes, and I'm glad now to be on the right side of this issue, trying to fight to help in any way that I can.

Q: How do you hold yourself accountable?

Azoulay: That's a good question. I mean, I think that one way I can hold myself accountable is to continue to do activist work and continue to try to educate people about what's going on. I feel like we're all pretty powerless except for what we can do. Like, you're a great citizen journalist. You're trying to get the word out. I run this movie theater. I'm trying to get the word out. I'm trying to program more films about the Palestinian plight. That's really all I can do. What I can do is regret the choices I made in the past and make better choices going forward.

Q: Why didn’t you tell [our mutual Palestinian friend] that you were living in her homeland?

Azoulay: I didn't know that it was relevant to what we were doing.

Q: How is it not relevant? She’s Palestinian.

Azoulay: She never asked me where I grew up. She never asked. I don’t know; I just never—I guess that’s my mistake. I guess that's a mistake that I made, but I came to her in good faith because I wanted to help her, and I tried my best to help her. I didn’t know—I guess that was a mistake, you’re right. I never really thought about it, but I guess I should’ve been more open about that.

Q: How do you think she reacted when I gave her that information?

Azoulay: Oh, I don't know.

Q: She was upset.

Azoulay: I mean—well, I should reach out to her….

Q: What made you decide to reveal it yesterday?

Azoulay: I wanted people to know that the reason why I’m so staunchly pro-Palestinian comes from a place of lived experience.

Q: Do you think it's justifiable for a Palestinian Gainesville resident to not wanna be around you because of your previous settlement?

Azoulay: Well, yeah, I mean it's up to them. I can't really make that decision for them. All I can do is let them know where I stand now is what's truly in my heart. If they feel uncomfortable, I can try my best to make them comfortable, but that's really all I can do.

Q: I think [our friend] had a right to know. Do you think Palestinian Gainesville residents have a right to know?

Azoulay: If they wanna know it, they can come and talk to me. I don’t see why not. I think it lends credence to my anti-Zionist perspective. It's like being there firsthand and seeing how bad it is. We're all learning.

Q: Alright, that's all the questions I had for you.

Azoulay: Thanks, Jack.